Back Home again 1944

By mid-1944, the War had moved on, and it was not necessary to keep the Bofors at Buna. The guns and crews were loaded onto the Duntroon. “I didn’t do gun duty on the Duntroon on the way home. I’d done it on the Queen Mary, the Andes and the Katoomba. My Sergeant, Bluey Page, told me to hold a broom and lean on it. If anyone asked anything, then he’d tell them it was my job to keep that section of the deck clean.”

“Then one of the twin propeller screws broke. The flag was sent up the mast upside down and I asked a sailor what was going on. He said it was a distress signal. The Captain told us that instead of 15 knots, we could only do four to five and that we were going into a four to five knot headwind and current. They sent out a Catalina to keep watch on us until we made Townsville on 9 June 1944 after a slow trip.”

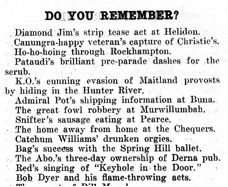

“After Townsville we went by train to a camp at Greta near Maitland. By now, most of us were a yellow colour from the yellow Atebrine anti-malaria tablets.” After a while back in Australia, with the effects of the tablets wearing off, it was estimated that 30% of his Battery fell ill with either malaria or dengue fever. Not to be outdone, Gunner Fryer got both at once and had a three-week spell in a hospital at Chermside near Brisbane. Upon recovery they had a short spell on the Gold Coast to recuperate further. “We could go for a walk each day down to the pub for a few beers.”

Upon recovery, the Bofors were variously set up at airfields and beaches along the coast from Brisbane to Tweed Heads. There were many troops either in the Brisbane region or passing through, so again sporting events such as athletics were organised ‘almost on a daily basis’. Gunner Fryer again showed his prowess at the 100 yards and, using some of the proceeds from the New Guinea book-making operation, managed to place a bet of three pounds each-way at odds of 12 to 1 in a big 440 yards event. “I was leading until the shadows of the post but then was narrowly beaten into 2nd place by an 18-year old who had won the Melbourne GPS 440 event only three months earlier”. Not a bad run for a recuperating veteran who was more than ten years senior to the new recruit!

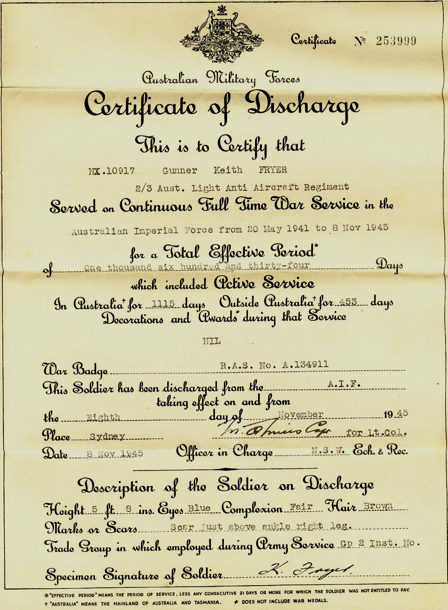

Gunner Fryer returned to Sydney where in December 1944 and January 1945 he attended courses leading to the qualification of a Teacher of Anti-Aircraft Gunnery. He attained top marks in those courses and in that capacity he taught gunnery drills and practice to officers at a military establishment near Randwick. “There were about 90-odd Gunners who were tested for this position. We had to be able to identify images of the Japanese, American and our planes which were shown to us very quickly. I didn’t get any wrong and came first and so got the job”. This meant he could get home leave two days a week.

Katanga and Flight were the two top horses of that era. Keith, in his Army uniform, saw the top jockey Darby Munro in a truck one morning and asked him for a tip. Darby said Katanga would win at Randwick that Saturday, winked and made as if he was curling his moustache. Keith decided to take Trix to the races and, “She scraped together about 4 shillings to put on Katanga. I got her odds of 7 to 1 but thought I was throwing her money away as Katanga only had a 16-year old apprentice jockey on him with little experience. I backed Flight at odds of 2 to 1. Ten minutes before the race started, the stewards announced that because Katanga was a strong and unruly horse, they had decided to replace the boy with ‘D. Munro’. Katanga’s price immediately shortened to favourite and I could have ripped up my ticket then. Obviously the Stewards were in on this ‘fixed race’ and Katanga duly beat Flight in a close finish.”